If you missed the previous editions, please find them here, here, here, here and here.Everything has a social cost. A digital economy is no different. The cost balance may be positive or negative—usually, it is a mixed bag.

People have complex relationships between inanimate tools, other people, and themselves. Digital systems can blur these lines and modify or amplify aspects of human behaviour. Digital communication in the form of social media is a good example. As we wrap up our series on Africa’s digital economy, we turn our focus to the social questions of building a digital economy.

To recap, “A digital economy is not just ‘the economic activity that results from billions of everyday online connections among people, businesses, devices, data, and processes’1 It is also how the creation and use of digital channels reshape economic, social choices and legal considerations in entire societies. Inevitably, a digital economy is about how physical actions, behaviours, communication, markets and choices are distorted by the use of digital infrastructure. In much the same way as a paved road that connects a struggling rural community to a thriving city can reshape the options for the residents of that community. From this view, it is easier to appreciate more of the nuance that shadows a digital economy.”2

A digital economy can create tremendous wealth and help uplift millions of people from poverty levels. It can support mire efficient service delivery systems. But it can also help entrench power. Economically, in the form of monopolies and oligopolies and politically, in the form of digitally enabled authoritarianism.

First, the good news

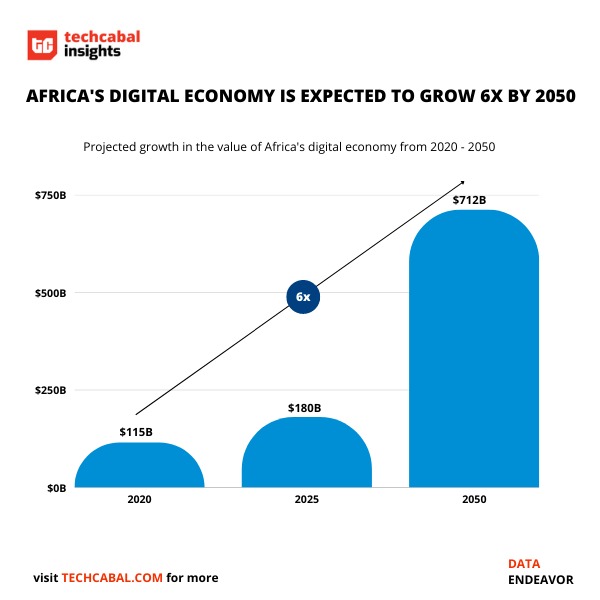

According to the e-Conomy Africa 2020 report published by the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and Google, Africa’s internet economy alone is expected to reach $180 billion by 2025, putting it at 5.2% of the continent’s current gross domestic product (GDP).3

In its “The Inflection Point: Africa’s Digital Economy Is Poised To Take Off” report, Endeavor Nigeria noted that Africa’s digital economy is already a $115 billion market. If Africa’s digital economy were a country, it would be the sixth largest economy in Africa. Only five African countries—Nigeria, South Africa, Egypt, Algeria and Morocco—have a GDP higher than the value of the combined digital economy of the continent.

This digital economy, which is still finding its feet, has attracted a lot of attention recently. Especially as the new fruits of the mobile communication revolution that swept the continent in the heydays of “Africa rising” in the late 1990s and early 2000s begin to ripen. You can almost draw a straight line from the first commercial pre-paid mobile phone call in many African countries to the astonishing levels of technology advancement and digital literacy that manifests in services like M-Pesa, Cellulant, Jumia and Main One’s data centres.

In the last five years, this growth has birthed a flourishing early-stage software startup market with investments poised to surpass last year’s $5 billion. With more people in Africa and outside paying attention to the state of the digital economy, a growing class of talented technicians and widespread adoption of digital tools, even African governments are beginning to pay closer attention. A number of countries have passed or are in the process of enacting laws to protect the emerging tech startup industry. The flip side of government attention is that public administrators are turning to this emerging sector to plug budget holes by taxing digital transactions or services.

In short, a lot is happening in Africa’s baby-stepping digital economy to warrant the optimism generously expressed on social media day in, and day out.

The costs: Digital economies exact a social toll

But technology does not exist in a vacuum. And prevailing narratives about the promise of Africa’s digital economy seem to gloss over the fact that adoption rarely happens wholesale. Indeed as Russell Southwood writes in his new book, Africa 2.0 – Inside a Continent’s Revolution:

“Technology is socially defined and not a separate entity from the social sphere. It may have ‘special powers’ but it will be users’ choice to use them or not.” 4

Not only is technology constrained by whether people choose to use them, how people choose to use digital tools, and how others respond to those choices are also important facets of how a digital economy operates in practice separate from theory. It is also important to note that how people choose to use digital services is also constrained by how these services are made and made available.

For example, people will be attracted to the anonymity and risk of cash or digital assets like Bitcoin in societies with a high deficit of public trust in official institutions. In the same vein, internet access is a gamble during elections in some African countries, which restricts how people use digital tools or whether they are even willing to transfer trust to digital entities. This gap in trust narratives is one of the costs a digital economy imposes on societies.

Read: little steps to financially savvy adults: Meet Little, the wallet app dedicated to kids.

A digital economy unlocks and is itself propelled by network effects. In this day and age, the primary yield of network effects is data. Tons of information about people and objects that were previously imperceptible or lost in the noise are produced in a tangible way that can be made sense of.

And taken advantage of.

It used to be that you needed to control the major arteries of one-to-many media, like radio or the newspaper, in order to perpetuate false information and propaganda. With social media, many-to-many communication is possible and a more complex and effective (colloquially called viral) way to spread good and bad news. The use of social media to direct hate at the Rohingya of Myanmar is an enduring example. Because it can often originate from state-linked authorities makes the situation even more complex to resolve short of an outright ban.

Coupled with the psychological impact of extended digital use, these effects of “network effects” are further compounded by the fact that as the user experience of technology gets progressively easier, the core skills required to decipher the language of digital systems becomes heavily abstracted. Excessive abstraction can create an exclusive high priestly class expanding the digital divide. Suddenly, it’s not about knowing how to build a website anymore. It is understanding the maths behind artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms. It is not a bad thing for progress. But it sharply increases the digital divide profile in a way that makes leapfrogging a requirement instead of a once-upon-a-time miracle.

In societies where the contours of overall well-being are still being traced, highly abstract concepts may be discarded to focus on the basics. This tradeoff is an important social cost to be aware of.

The public institutions, development organisations and private enterprises working to expand the reach of digital transformation may omit or incorrectly model issues like the aforementioned. But the truth is that consciously or not, people weigh the tradeoffs as they go about their daily life.

Some of the more thoughtful Africa-focused venture capital investors have highlighted how this tension plays out in Africa’s large retail segments. It is true that this constant ebb and flow is a drag on digital transformation. But it is also a constant reminder that there are unresolved social dynamics that impose on plans for a digital anything.

Stepping back ≠ “A step back”

If you have been following this series on Africa’s digital economy, it will be obvious that this is all a very macro discussion. The specifics are infinitely more complicated. But the benefit of broad brushstrokes—of the macro—is that it outlines the general context. Macro thinking is a helpful way to understand how complicated modern economic systems work. Within this proper context, the details can then be painted in.

The future of technology—the next wave—in Africa will be a complex and unequal affair as digital systems sweep through the continent and a coherent political economic interpretation develops. Wise governments and entrepreneurs will care about the trees, but they will realise the power of the forest. And that the forest, like the tree, is a living organism. To put it simply, Africa will only create and unlock true value from digital transformation when we realise the unique ecology of digital systems as much as we value individual sections like payments for example.

The unlocked value from a digital economy can then be accessed or abused through individual “trees” or verticals like retail, healthcare, education, financial services and governance. As it is today, most activity in public policymaking in Africa focus on specific trees in the digital ecosystem. A digital healthcare delivery system, for example, has value, costs and risks that extend beyond hospitals. Education technology has benefits and risks beyond virtual classrooms and digital financial inclusion that is tied to universal biometric ID systems creates more value and risk beyond simplifying payments. “Everyone plays a piece and there are melodies.”

It is these linkages that automatically form as sections of the formal economy are being digitised that create the social risks associated with digital economies. Again, I want to stress this: a digital economy is not the ICT sector’s contribution to the GDP.

It is not the map of startups, funding raised by startups, or a national digital strategy. It is subtle and not-so-subtle ways that digital tools, infrastructure, protocols and e-governance reshape human interactions and economic choices in a society. It is how digital eats, digests and replaces traditional economic interactions. It is how WeChat and Beijing co-function to police behaviour with economic disincentives. It is how social media firms in the US react to misinformation and collaborate with the state to curate the conversation. It is how unilateral sanctions can undermine the health of Huawei and risk splitting connectivity standards for 5G infrastructure.

A disjointed approach that treats the trees in digital ecosystems as separate entities and loses sight of the forest will yield short-term value per tree. But ultimately, the risks, especially the social costs, will coalesce and short-term gains will be wiped out.

It is the responsibility of everyone—not just government or private entrepreneurs—to create the paradigms that will identify and contain these risks at a system level. In many ways, this is one more example of how astonishingly human digital economies are.

Read: Isimi Lagos: the city of the future

Dear reader!

2022 has been a wild ride in the African tech ecosystem, and we have played a critical role in covering the players, the human impact and the business of tech in Africa. We have provided the content, reported the data, asked the questions, and organised events to help you understand how tech is changing Africa.

Now it’s time to take stock. Please take a few minutes to share your thoughts on how we did in 2022 and what we should do better in 2023. By filling this survey, you stand the chance to win a $50 gift card!

Thank you for your time!

Click here to tell us how we did in 2022References

[1] “What is a digital economy?” Deloitte Malta https://www2.deloitte.com/mt/en/pages/technology/articles/mt-what-is-digital-economy.html

[2] Augustine Abraham “The Next Wave: A digital economy is, above all, physical” TechCabal, Oct 10, 2022https://techcabal.com/2022/10/10/digital-economy-anatomy/

[3] “e-Conomy Africa 2020 – Africa’s $180 billion Internet Economy Future” Google, IFC, n.d https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/publications_ext_content/ifc_external_publication_site/publications_listing_page/google-e-conomy

[4] Southwood Russell, “Africa 2.0 – Inside a continent’s revolution” Manchester University Press, 2022

We’d love to hear from you

Psst! Down here!

Thanks for reading The Next Wave. Subscribe here for free to get fresh perspectives on the progress of digital innovation in Africa every Sunday.

Please share today’s edition with your network on WhatsApp, Telegram and other platforms, and feel free to send a reply to let us know if you enjoyed this essay

Subscribe to our TC Daily newsletter to receive all the technology and business stories you need each weekday at 7 AM (WAT).

Follow TechCabal on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and LinkedIn to stay engaged in our real-time conversations on tech and innovation in Africa.

Abraham Augustine,

Senior Writer, TechCabal.